About Mountain Images

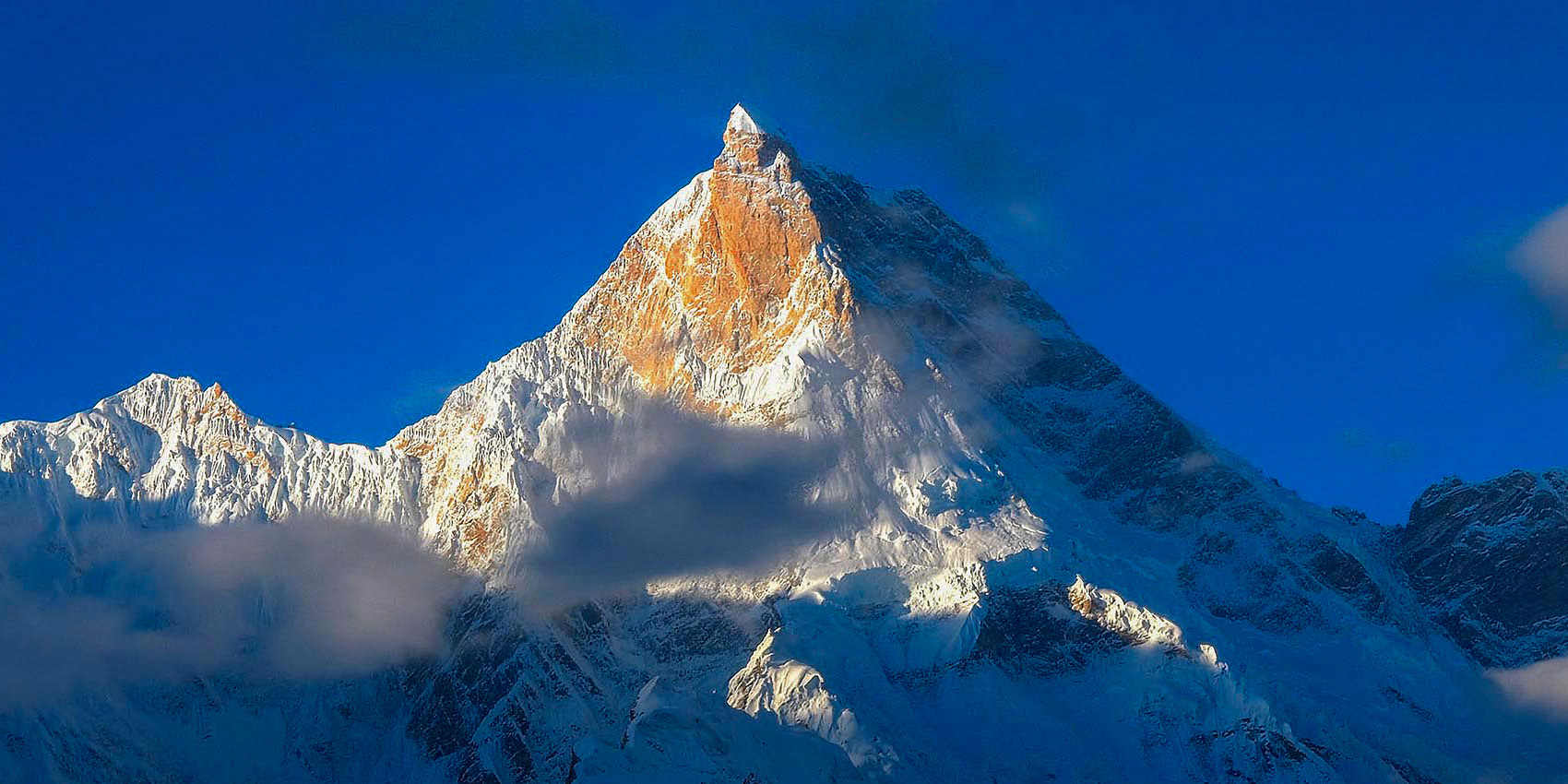

Mountain Images are a specialist publisher of high quality mountain prints - a Scottish based business established in 1983 by Ian Evans - a mountaineer, photographer and writer on the mountains of Britain and The Himalaya.

Throughout his life Ian has been climbing and photographing mountains in the UK, the Alps and particularly The Himalaya. He is a sensitive observer of landscape and light; his love for, and understanding of the mountain environment is reflected in every image.

Ian lives and works in the village of Invermoriston in the Scottish Highlands from where he enjoys easy access to Scotland's finest mountains.